Recently, I discovered a memory exhaustion vulnerability (CVE-2025-53020, Apache’s Security Report) in Apache HTTP Server’s HTTP/2 module that made Apache duplicate headers sent by the client. Using HPACK compression, some HTTP message tricks and a little optimization, this vulnerability could be exploited to create a 4000x amplification attack - that causes the server to allocate ~8MB for only a 2KB request the attacker sends.

Combined with HTTP/2’s concurrency and Apache’s delayed stream cleanup, this allows attackers to consume gigabytes of memory and cause an OOM crash, with minimal network traffic.

A Little Bit of Background

Apache HTTP Server is the 2nd most common server on the internet, with between 25%-32% of the market (suppressed only by nginx) and it supports HTTP/2 using a module called mod_http2.

Plan

Here’s what we will uncover: First we’ll dig into where this vulnerability hides in Apache’s code, then we’ll see how to exploit it using HPACK compression and get a good amplification factor, we’ll optimize the attack so that we could use this amplification many times by understanding the limitations Apache forces on us, and finally we’ll explore how Apache’s cleanup timing makes everything so much worse (and better for us).

Background

Apache’s APR (Memory) Pools

Before we dive into the vulnerability, we must understand how Apache manages memory. Apache uses its own memory pooling system called APR pools - think of them as memory buckets with different lifetimes.

When using APR pools - instead of calling malloc() and free() for every little allocation, you allocate memory from a pool. When you’re done with everything in that pool, you destroy the entire pool in one shot. It’s fast, prevents memory leaks, and is easy to use.

Apache has different pools for different objects - for example:

- Session pools: Live for the entire HTTP/2 connection

- Stream pools: Live for individual HTTP/2 streams (requests)

How does Apache process HTTP/2 headers? Unlike HTTP/1.x where headers come as nice text lines like Content-Type: application/json, HTTP/2 headers are compressed using HPACK and arrive as binary data in an object called HEADERS frame - which holds the headers part of the HTTP request.

The key difference is: in HTTP/1.x, the complete HTTP message arrives “as is” - you can literally read the request line by line and parse it directly. But HTTP/2 is different. The same HTTP semantics (method, headers, body) are there, but they’re encoded in a binary format, compressed, and could be split across multiple frames. So instead of parsing text directly, Apache needs to reconstruct the familiar HTTP request structure from these binary frames - this functionality is provided by a third party library called nghttp2.

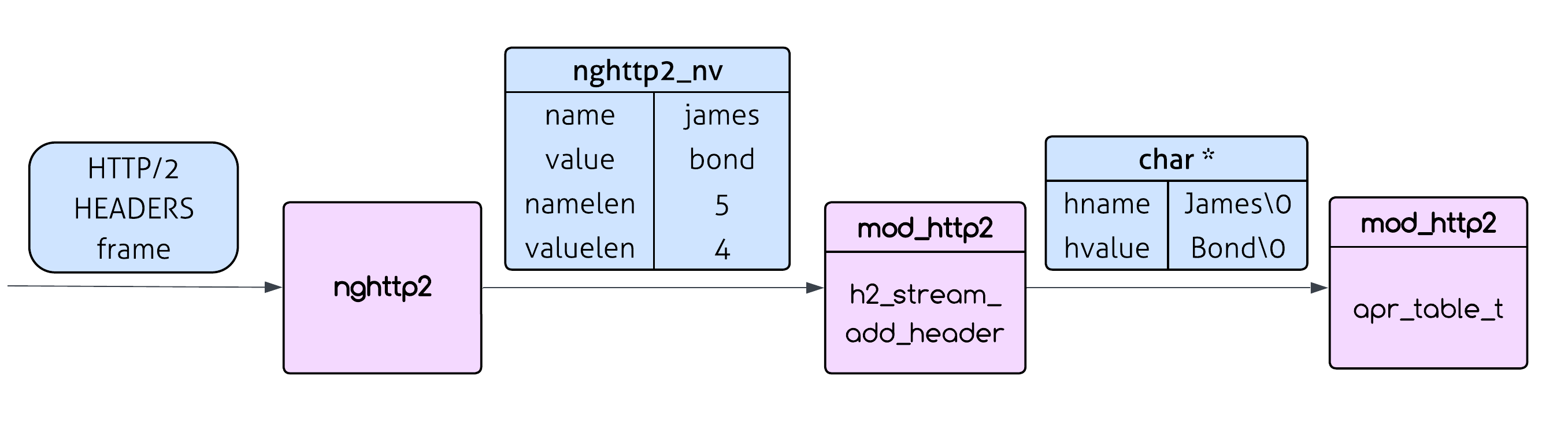

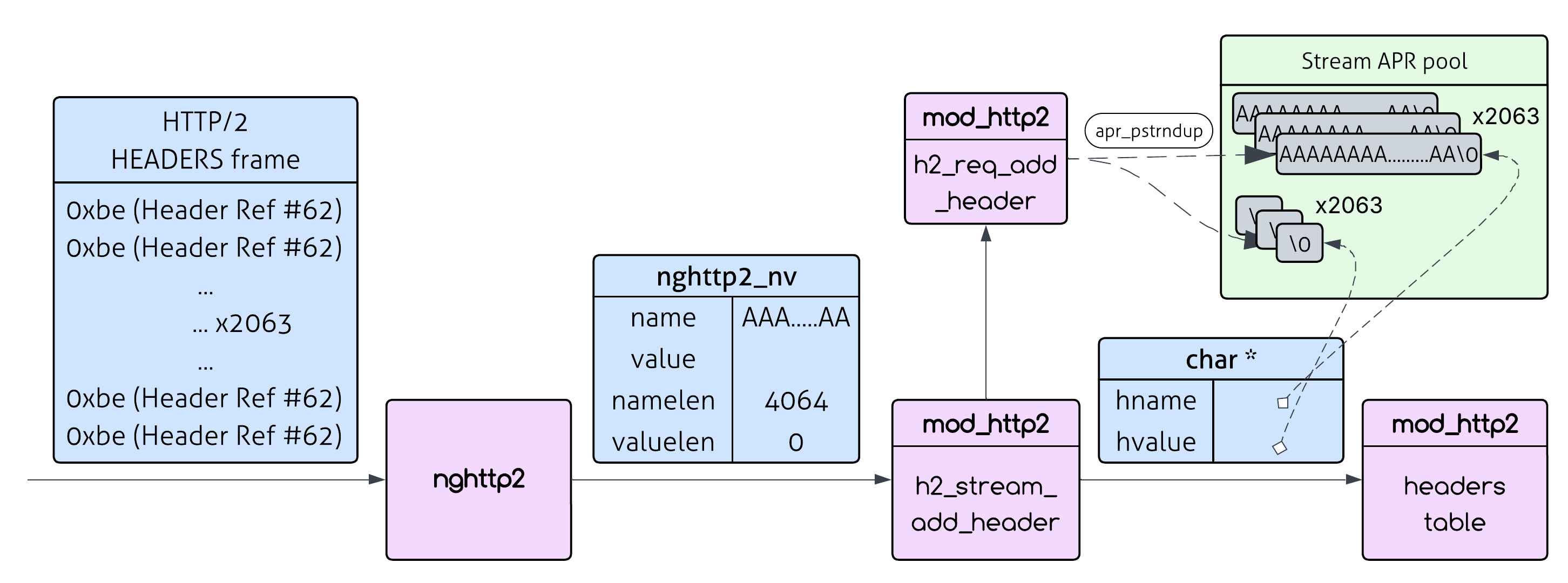

Nghttp2 does the heavy lifting of handling the HTTP/2 encoding and compression and then calls back into mod_http2 (the Apache module responsible for HTTP/2) with individual header name/value pairs (this is done using the on_header_cb callback). These name/value pairs aren’t the typical null-terminated C strings. Instead, they come as nghttp2_nv structs containing raw byte pointers and explicit lengths (namelen and valuelen).

When mod_http2 receives the name/value pairs, it calls h2_stream_add_header(). This function converts these raw byte arrays into proper C strings, performs some formatting (camel case for the header name for example) and inserts them into Apache’s traditional apr_table_t struct - which is a table that holds the headers of the request - the same struct that is used for HTTP/1.x headers. Only then can Apache build the familiar HTTP request structure that the rest of the server expects.

The Vulnerability

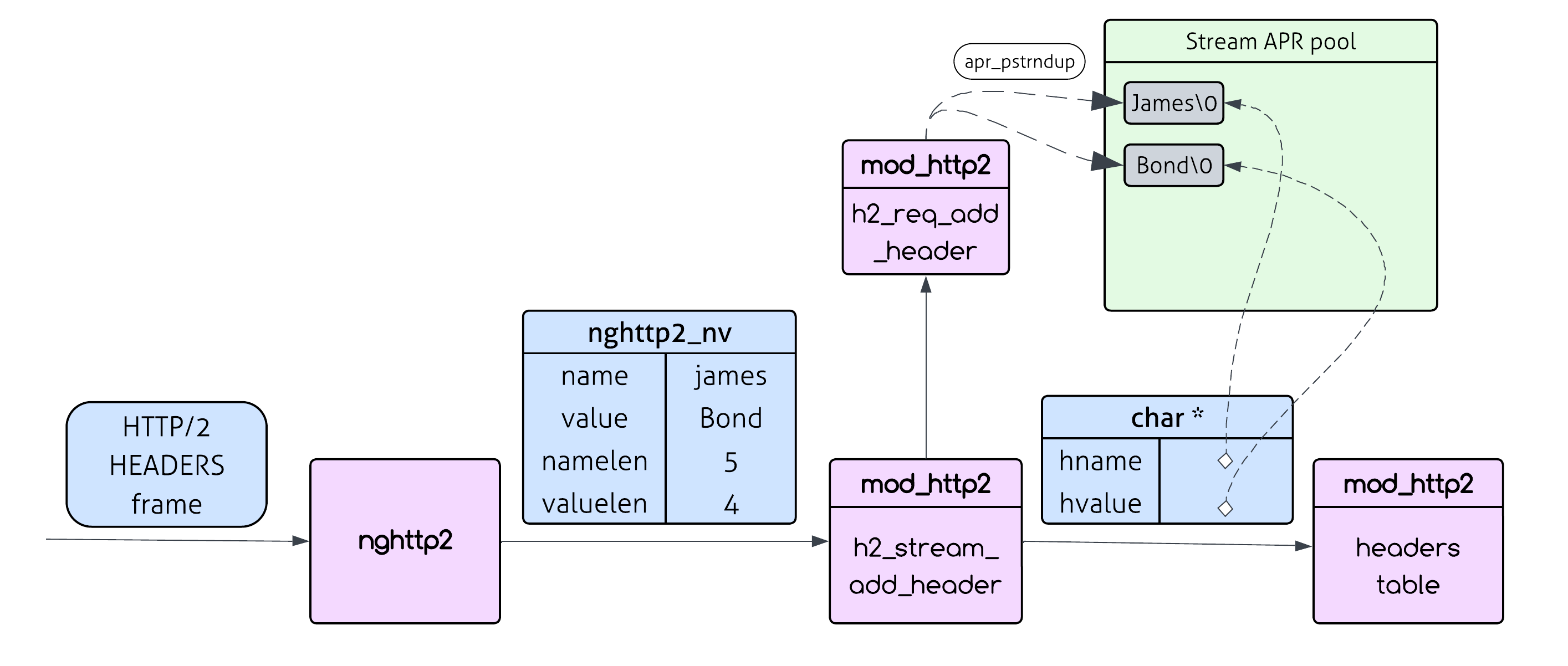

When Apache processes each HTTP/2 header, it takes the header data from nghttp2 and works with it to build the HTTP request structure. But there’s a mismatch: nghttp2 provides raw byte pointers with explicit lengths (not null-terminated), while Apache’s internal APIs expect traditional null-terminated C strings.

So Apache can’t just use those nghttp2 pointers directly - not only does that data belong to nghttp2 (and this data will be freed when reading the next header), but Apache needs null-terminated versions to work with its existing string handling code. This means Apache has to make its own null-terminated copies during header processing.

h2_stream_add_header calls h2_request_add_header which calls h2_req_add_header (in h2_util.c), which performs the conversion:

static apr_status_t req_add_header(apr_table_t *headers, apr_pool_t *pool,

nghttp2_nv *nv, size_t max_field_len,

int *pwas_added)

{

char *hname, *hvalue;

const char *existing;

// some code

// Convert the header name to a null-terminated string

hname = apr_pstrndup(pool, (const char*)nv->name, nv->namelen);

h2_util_camel_case_header(hname, nv->namelen);

// some code

// Convert the header value to a null-terminated string

hvalue = apr_pstrndup(pool, (const char*)nv->value, nv->valuelen);

apr_table_mergen(headers, hname, hvalue);

return APR_SUCCESS;

}

See those apr_pstrndup() calls? Each one creates a complete copy of the header name and value in the stream’s pool (remember that Apache can’t call apr_table_mergen with nv->name and nv->value since they are not null terminated and also need to be formatted beforehand). For every single header that comes in from nghttp2, Apache duplicates it - that’s the core of the vulnerability.

You might think, “So what? Every header you send should take up memory on the server - that’s supposed to happen. The HTTP request you send to the server will be allocated in the server.”

You are not wrong - those duplications are not redundant or unnecessary: those char * null terminated strings are the same strings that will be inserted into the headers table using apr_table_mergen at the end of the function.

However, you are thinking about it in HTTP/1.1 terms, but we are in the HTTP/2 universe, and that gives us some interesting tricks to use.

Let’s start exploiting it.

Exploitation

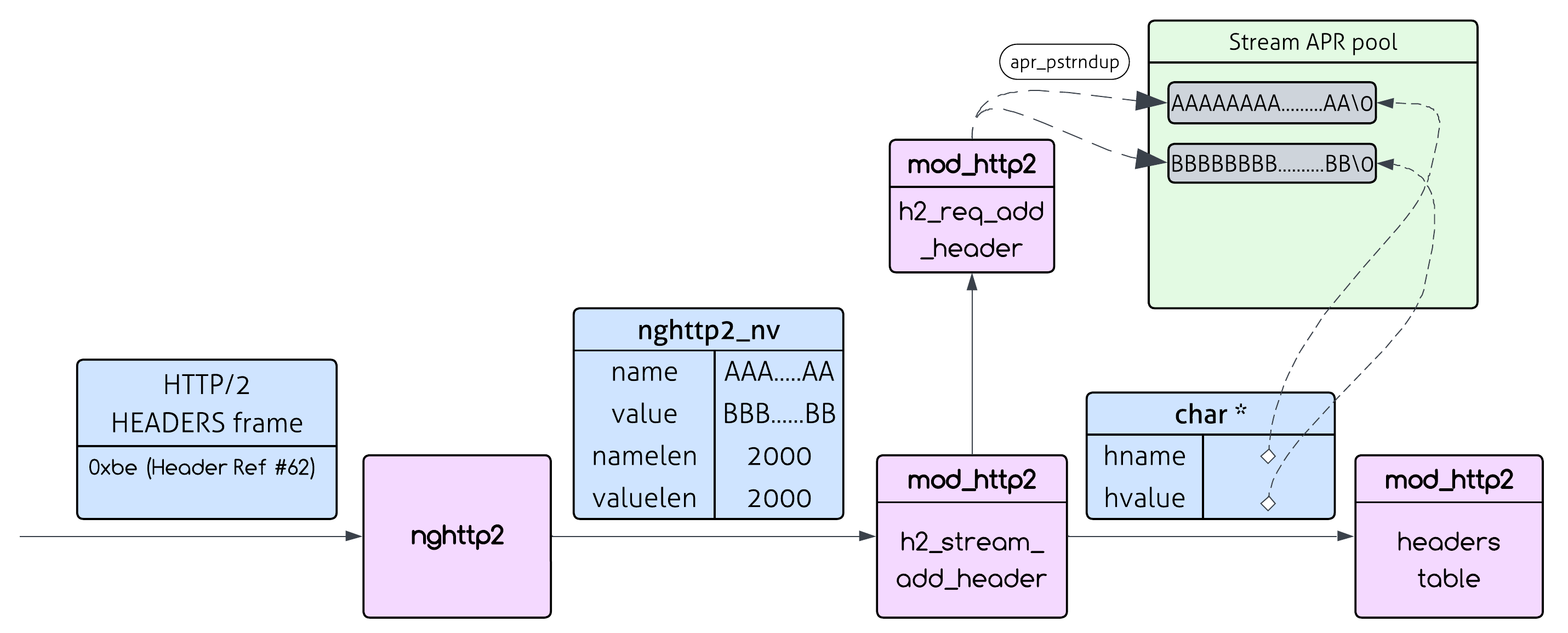

HPACK Amplification: The Secret Weapon

The first thing we need is a way to tilt the balance in our favor - sending X bytes of headers to the server and causing it to allocate X bytes of data is just normal protocol behavior, and we can’t do much damage with a 1:1 ratio. Luckily for us (and for the performance of the internet), HTTP/2 uses HPACK compression for headers, which includes a dynamic table that both client and server maintain. This table allows frequently used headers to be stored and referenced by index instead of sending the full header each time. Makes sense, right? Why send the same User-Agent header in every request when you can just say “use header #42 from our shared table”?

The dynamic table has a limited size (typically 4096 bytes), and when it fills up, old entries get evicted to make room for new ones.

So the basic way to exploit this is:

-

Step 1: Fill the dynamic table with a massive header field (name/value pair)

This header name can be ~4000 bytes long (since there are static entries in the table), so it takes up almost the entire 4096-byte dynamic table. It gets assigned an index (let’s say index 62 - which is the first dynamic index in the table) and now dominates the table.

-

Step 2: Reference it with just one byte

Instead of sending the full 4000-byte header field again, we can now reference it with just a single byte: 0xbe (which represents “indexed header field” for index 62).

So by sending “1 byte” (not including the TCP/IP and HTTP/2 frames bytes) we cause an allocation of 4000 bytes on the server. Still, that’s standard HTTP/2 behavior - this so called “amplification” is a very important feature of HTTP/2 - still not a vulnerability.

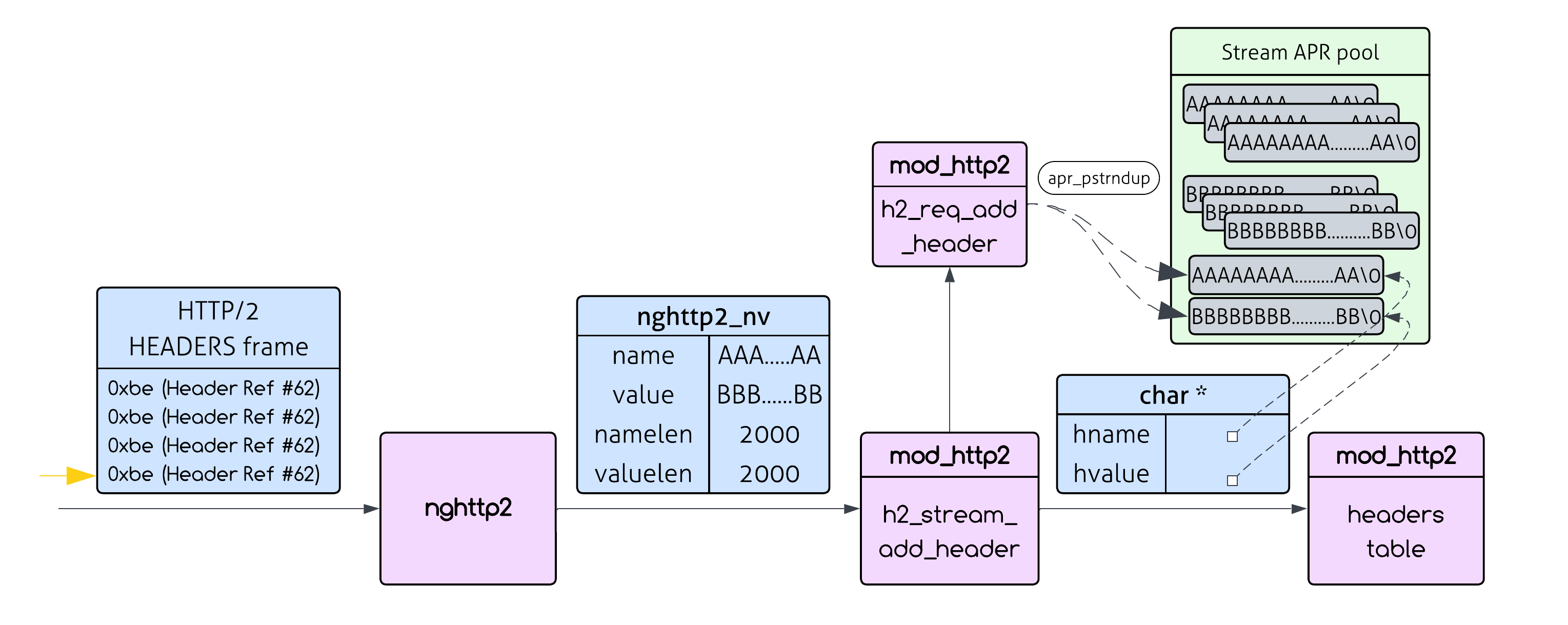

But what if we will do that many times?…

My suggestion is:

- Step 1: Fill the dynamic table with a massive header field (name/value pair)

- Step 2: Reference it repeatedly with just one byte

- Step 3: Cause many server side allocations with an amplification of 4000x.

Now we can send hundreds of these single-byte references in one HTTP/2 frame:

0xbe 0xbe 0xbe 0xbe 0xbe 0xbe 0xbe 0xbe ...

Each 0xbe byte forces Apache to:

- Call

h2_stream_add_header() with the full 4000-byte header field

- Call

apr_pstrndup() to duplicate the 4000-byte header in memory

1 byte of network traffic = 4000 bytes of server memory consumption. That’s a 4000x amplification!

However, this works only when we reference the same header from the table. If we use a different header, we have to send it as-is - without any HPACK shortcuts.

So the way to exploit the vulnerability is to send the same header field over and over again, with HPACK references.

But what happens when we send the same header multiple times? Is it even allowed?

Fortunately, the HTTP message format allows for duplicate headers, and when the server receives multiple duplicate headers, it concatenates them.

This means that if we send multiple headers with the same name:

Header-Name: value1

Header-Name: value2

Header-Name: value3

Apache will eventually merge these into a single header (Header-Name: value1, value2, value3), but here’s the sting: each duplicate header gets copied separately during processing. So “Header-Name” gets duplicated three times in the stream pool, even though the final result only needs it once.

So we could repeat this pattern many times within a single HTTP/2 HEADERS frame. Each repetition forces another 2 apr_pstrndup() calls, creating memory copies of both the name and value - with an amplification factor of 4000x - that persist until stream cleanup.

An amplification factor of 4000x is awesome, but another important factor for the success of the attack is how many times could we use this amplification? If we are allowed to use it only several times, the impact will be negligable.

Will Apache let us send the same header an unlimited amount of times?

Sadly (for us), there is a limit on headers length - which gives us another complication.

Next we will understand what we are constrained to, and try to find the best possible header to use so that our attack will have significant impact.

Repetitions, Repetitions, Repetitions

Now we ask ourselves what header (name+value) should we send, and with how many repetitions?

Each repetition will result in another duplication of the name and value in memory.

So a high number of repetitions means bigger impact. A low number means we failed.

Let’s go back to the req_add_header code, but this time I’ll show you the limit check that we are constrained to:

static apr_status_t req_add_header(apr_table_t *headers, apr_pool_t *pool,

nghttp2_nv *nv, size_t max_field_len,

int *pwas_added)

{

char *hname, *hvalue;

const char *existing;

// some code

// Convert the header name to a null-terminated string

hname = apr_pstrndup(pool, (const char*)nv->name, nv->namelen);

h2_util_camel_case_header(hname, nv->namelen);

existing = apr_table_get(headers, hname);

if (max_field_len) {

// This is the header length check

if ((existing? strlen(existing)+2 : 0) + nv->valuelen + nv->namelen + 2

> max_field_len) {

return APR_EINVAL;

}

}

// Convert the header value to a null-terminated string

hvalue = apr_pstrndup(pool, (const char*)nv->value, nv->valuelen);

apr_table_mergen(headers, hname, hvalue);

return APR_SUCCESS;

}

Let’s break it down:

max_field_len is controlled by the LimitRequestFieldSize configuration, which defaults to 8190 bytes.

existing = apr_table_get(headers, hname);

apr_table_get gets the value associated with header hname from the table headers. If it doesn’t exist, it will return null.

Let’s break down the if statement:

if ((existing? strlen(existing)+2 : 0) + nv->valuelen + nv->namelen + 2 > max_field_len)

This basically checks if: exisiting_value_len + 2 + new_value_len + name_len + 2 > 8190

The +2 accounts for the ', ' separator that gets added between duplicate values.

When we pass that check, apr_table_mergen concatenates our new value to the existing one with ', ' in between. So for every header we add, strlen(existing) increases by nv->valuelen + 2.

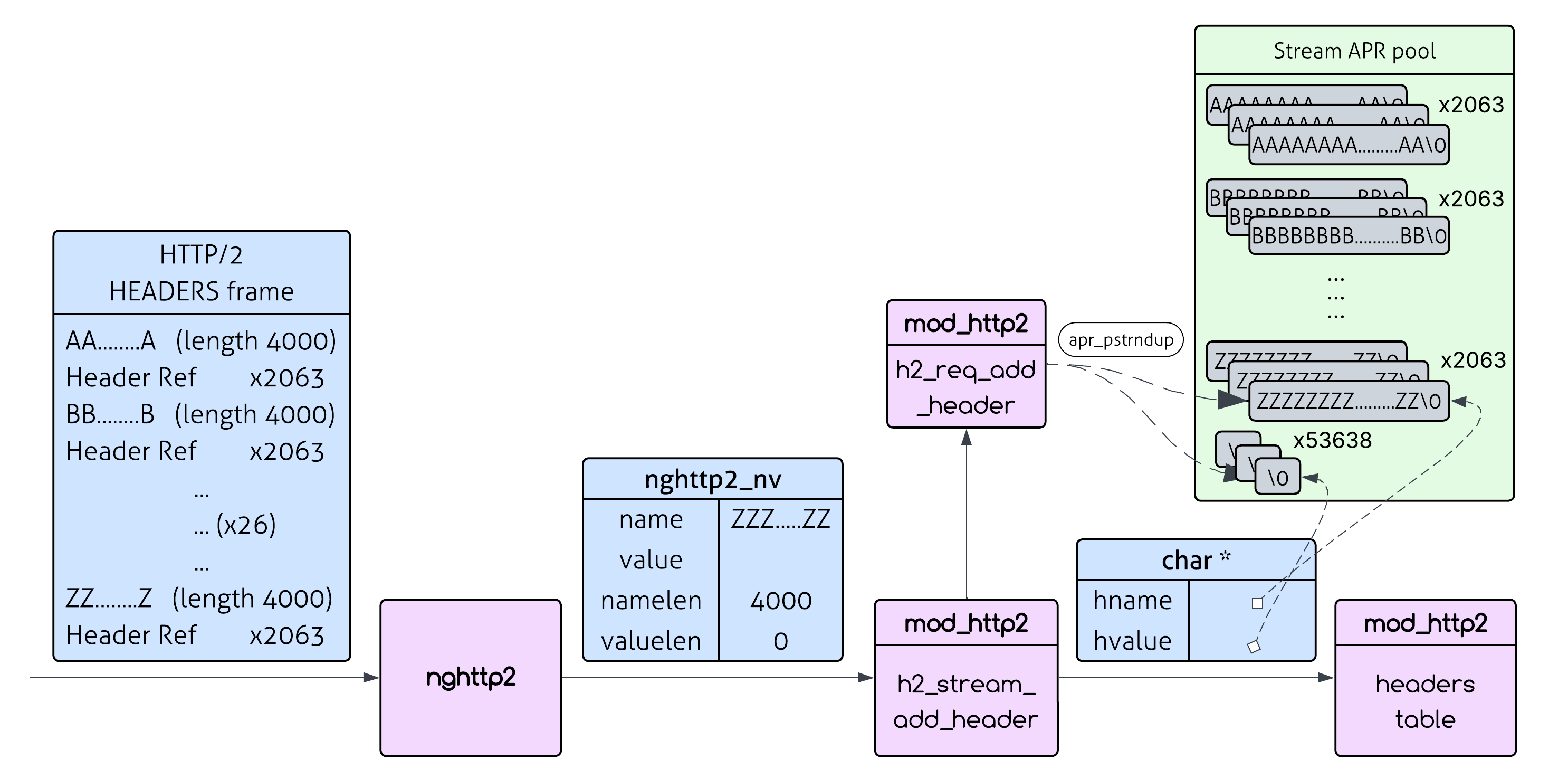

An obvious way to optimize it is to choose the value to be a single char. That way strlen(existing) will increase by only 3 with each repetition.

A dedicated researcher that wants to squeeze everything they can from this vulnerability will go to the code and check if there are possible shenanigans to exploit. Bypassing the addition of ', ' is not possible. However, an inspection of the code shows that it allows for empty values to be sent - that means that strlen(existing) will increase by only 2 for every header repetition. I know that looks like a small improvement, but that’s a 50% improvement over using single-character values, and will make our attack significantly stronger.

We are left with the following optimization strategy:

- Use empty values (

nv->valuelen=0): This means each repetition only adds 2 bytes to strlen(existing)

- Maximize namelen: Since we copy the name every time, longer names = more memory allocated

Now, you could believe me when I say that the maximum name length we can use is 4064 (because of HPACK header table size constraints) and that given that, the best option for the number of repetitions is 2063 (for the skeptic/curious reader - the calculations are shown in the appendix).

In this case, since every header repetition creates an allocation of size namelen, our total memory consumption is:

namelen * number_of_repetitions = 4064 * 2063 = **8,384,032 bytes** (~8.38MB).

We consume those ~8.38MB of server memory by sending only ~2KB of network traffic - that’s a 4000x amplification utilized to a significant impact!

Who said we have to settle for just one header name? When we hit the repetition limit with one header, let’s just switch to a different header and do it again!

This slightly hurts our amplification factor since we have to send the new header without HPACK compression - but HPACK uses Huffman encoding, so a header like 'a' * 4064 actually encodes to about 2565 bytes rather than the full 4064.

There are limits though - Apache enforces limits on HTTP/2 frame sizes (specifically the number of CONTINUATION frames). After working through the math, we can fit about 26 different headers in one request, resulting in ~217MB of server memory consumption from ~133KB of network traffic (amplification factor of ~1630x).

Ok, we squeezed everything we could from a single request, Let’s move on.

Now we are going to look at a way to multiply the impact of the attack.

Multiplying The Impact

Let’s recap what variants we have so far:

- Send a 2Kb request and consume 8.37MB on the server.

- Send a 133Kb request and consume 217MB on the server.

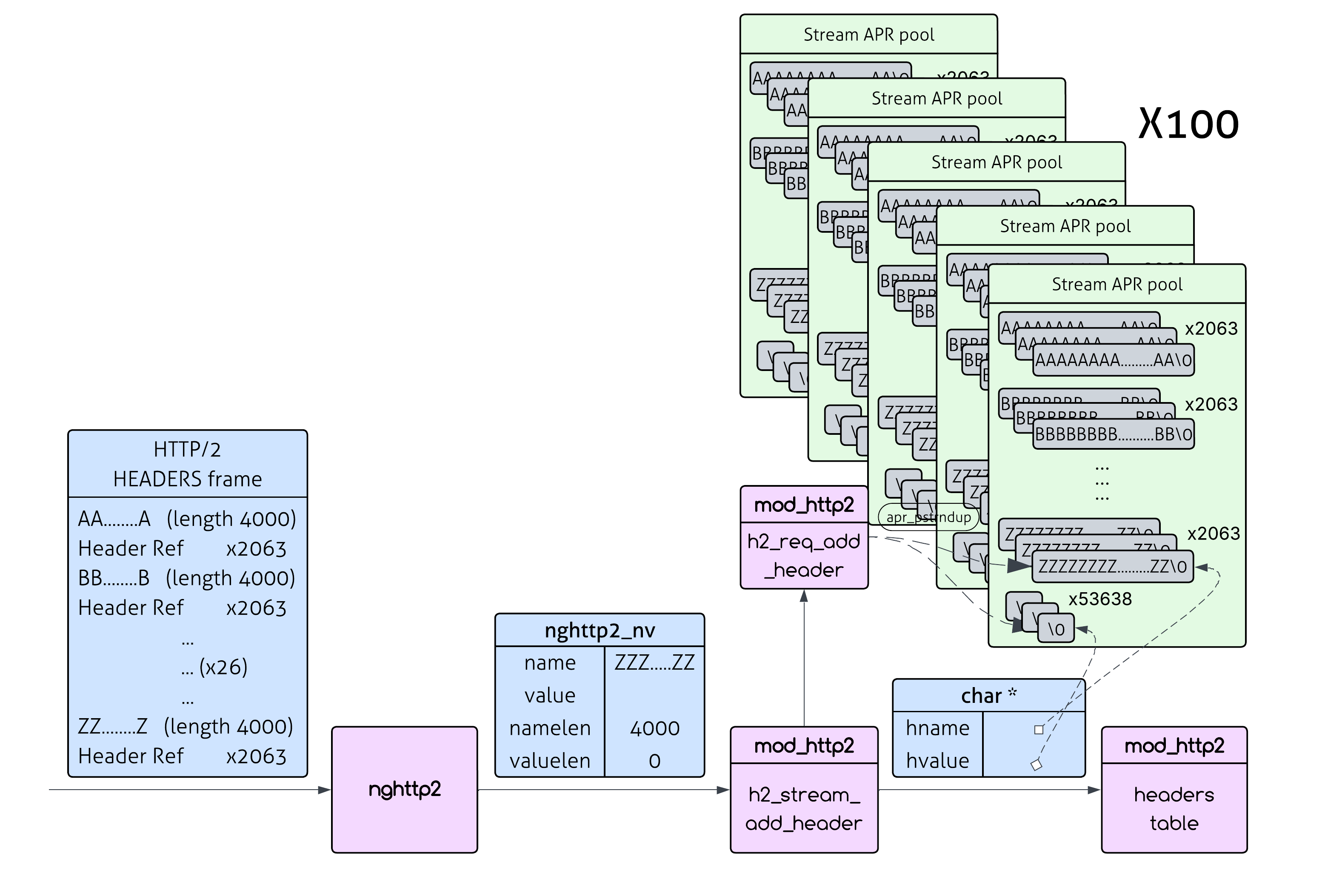

We have yet to use the second feature that makes HTTP/2 so great - stream concurrency. Streams are virtual channels upon which requests are sent. By using stream concurrency we are able to send 100 requests concurrently (the default maximum allowed in HTTP/2).

And just like that - we can make the impact of the attack 100x stronger!

It’s not that simple but that’s the general idea. Let’s get into it.

Using Multiple Streams

We have a small problem - the attack will be 100x stronger only if those requests will “live” at the same time.

But we are sending requests one by one, so we can’t guarantee this. But who says we have to send them one by one?

We can actually send them in an interleaving way - making all of them exist concurrently.

But we have an even better way to do that - using yet another HTTP/2 trick - since headers go over streams, and are not the same object in HTTP/2, we can say we have finished sending the headers (which will cause Apache to parse them) but we don’t have to declare we finished sending the stream.

My suggestion is:

Using HTTP/2 we can do the following:

- Step 1: Open a stream and send the headers over it.

- Step 2: Declare we are done sending the headers (using the

END_HEADERS frame). Don’t declare the stream is finished (using the END_STREAM flag).

- Step 3: Repeat.

Apache introduces request timeouts to prevent malicious clients from keeping connections open indefinitely.

In HTTP/2 the variable that is responsible for this is H2StreamTimeout and it is described as “Maximum time waiting when sending/receiving data to stream processing”. Its default value is 1 second.

So we need to send as many requests as possible within 1 second - after which we will get a timeout.

We could have finished here, but if we dive a little deeper, we could actually make the attack even stronger.

What we’re trying to do now is to make requests “live” at the same time.

But more precisely, what we need to do is to make the memory allocations “live” at the same time.

In order to do that we need to understand how streams are destroyed, and then make them last as long as we can.

Stream’s Lifetime

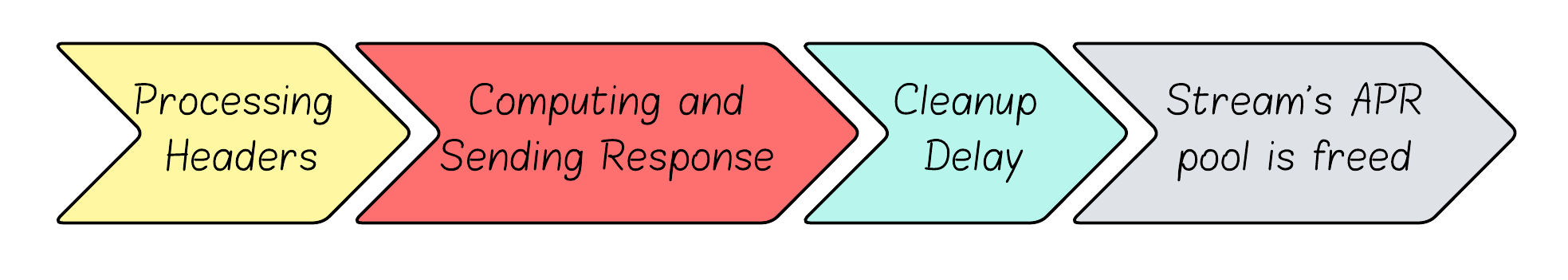

Remember that all of the memory allocations happen in a stream’s memory pool? Well, the memory pool of a stream only gets destroyed when the function h2_stream_destroy is called. But here’s the kicker: it doesn’t get called immediately after header processing. It can only be called after the entire stream is complete - meaning the response has been computed and sent back to the client.

Even then, h2_stream_destroy is called by another function - c1_purge_streams, which is only called at specific intervals when the HTTP/2 session enters the H2_SESSION_ST_IDLE state. This delayed cleanup is probably done for performance reasons - batch processing is more efficient than destroying streams one by one.

For normal operations, this delayed cleanup isn’t a problem. But what we’re doing isn’t normal…

So the cleanup delay already gives us an edge - which is actually very significant. When I ran my PoC against a simple Apache server that returns “Hello World!” (which means the processing time is negligible) - I got memory increase of between 1GB-1.6GB (Recall that without the delay only 837MB could have been allocated on the server).

Previously we have optimized the processing of headers to consume as much memory as we can. We also were glad to hear that there is a cleanup delay. We have 1 more part to focus on - the “Computing and Sending Response”.

How can we make the computing of the response longer? Actually that’s easy - let’s pick a resource with high processing time!

Turns out that the response computation is not subject to the H2StreamTimeout parameter, it is subject to regular Apache timeout mechanisms.

So we now have the final recipe for the attack:

- Open multiple streams simultaneously - Send requests with our amplified headers, without closing the streams.

- Each stream allocates its own memory - Every stream has its own pool, so memory consumption multiplies

- Choose a resource with high processing time - Making the stream lifetime longer.

- Delayed Cleanup - Since streams don’t get cleaned up immediately, they all keep their memory allocated simultaneously.

How The Patch Works

Now for the good news - the fix is actually quite elegant! The Apache developers solved this by introducing scratch buffers that eliminate the need for all those memory-hungry apr_pstrndup() calls.

The Core Problem (Before the Patch)

Remember what was happening in the original code:

// For every single header, Apache did this:

hname = apr_pstrndup(pool, (const char*)nv->name, nv->namelen); // Allocate + copy name

hvalue = apr_pstrndup(pool, (const char*)nv->value, nv->valuelen); // Allocate + copy value

apr_table_mergen(headers, hname, hvalue);

Each header triggered two memory allocations from the stream pool, and those allocations stuck around until stream cleanup. With our HPACK attack, this meant thousands of 4KB allocations piling up in memory.

The Solution: Scratch Buffers

The patch introduces a clever solution - reusable scratch buffers that are allocated once per HTTP/2 session and then reused for all header processing:

// In h2_session struct:

typedef struct h2_hd_scratch {

size_t max_len; // Maximum header field size (LimitRequestFieldSize)

char *name; // Reusable buffer for header names (max_len+1 bytes)

char *value; // Reusable buffer for header values (max_len+1 bytes)

} h2_hd_scratch;

How It Works

Instead of allocating new memory for each header, Apache now:

- Copies header data into scratch buffers (temporary, reusable space)

- Processes the header using the scratch buffer contents

- Reuses the same scratch buffers for the next header

Here’s the new code flow:

// Copy into reusable scratch buffers (no allocation!)

memcpy(scratch->name, nv->name, nv->namelen);

scratch->name[nv->namelen] = 0;

memcpy(scratch->value, nv->value, nv->valuelen);

scratch->value[nv->valuelen] = 0;

// Process using scratch buffer contents

apr_table_mergen(headers, scratch->name, scratch->value);

Why This Fixes the Vulnerability

Before the patch:

- Each header → new memory allocation from stream pool

- 4000 duplicate headers → 4000 separate allocations

- Memory persists until stream cleanup

- Using HPACK amplification - this was effortless for us

After the patch:

- Each header → reuse existing scratch buffers

- 4000 duplicate headers → same 2 scratch buffers reused 4000 times

- No additional memory allocated beyond the initial scratch buffers

The attack that could previously consume gigabytes of memory now consumes just a few kilobytes - the size of the scratch buffers themselves. The fix is elegant because it’s bounded (maximum 2 × LimitRequestFieldSize bytes per session), eliminates allocation overhead, and requires no changes to Apache’s existing header processing logic.

Final Words

This vulnerability highlights a broader challenge in HTTP/2 security: the protocol’s efficiency features can become attack vectors when combined with traditional memory management patterns.

A proof-of-concept for this vulnerability is available on my GitHub page for those who are interested (There is also an interesting patch I needed to do there to make the python library behave like I wanted).

Special thanks to Stefan Eissing, the Apache HTTPD Server’s HTTP/2 module project lead, for his exceptionally professional and swift response throughout the disclosure process. His collaborative approach and technical expertise made this one of the most productive security research experiences I’ve had. I’m also grateful for his kind words about this research on his blog.

Appendix

Math Calculations For The Skeptics

You either finished the post and now want to see the calculations out of interest, or you didn’t believe me. Either way - let’s get to it:

Remember earlier we said every header we add increases the length of existing by 2?

That’s almost precise (which was good enough for the general explanation - but you insist on precision). It’s true for the 2nd or later additions. Let’s see why:

Header 1:

existing = null (no previous headers)- Check:

0 + 0 + namelen + 2 ≤ 8190 → namelen ≤ 8188 ✓ (passes)

- After adding:

existing = "" (empty string)

Header 2:

existing = "" (length 0)- Check:

0 + 2 + 0 + namelen + 2 ≤ 8190 → namelen ≤ 8186 ✓

- After adding:

existing = ", " (length 2)

Header 3:

existing = ", " (length 2)- Check:

2 + 2 + 0 + namelen + 2 ≤ 8190 → namelen ≤ 8184 ✓

- After adding:

existing = ", , " (length 4)

General pattern: Before adding header number i (where i ≥ 2), existing has length 2*(i-2)

The check for header i becomes: 2*(i-2) + 2 + 0 + namelen + 2 ≤ 8190

Which simplifies to 2*i + namelen <= 8190

So the maximum number of repetitions we can have is (8190 - namelen)/2

Every header repetition creates an allocation of size namelen, so our total memory consumption is:

namelen * number_of_repetitions = namelen * (8190-namelen)/2

The value that maximizes this function is namelen=4095. However, namelen cannot be bigger than 4064, so this is the best value we can use.

Therefore, the number of repetitions will be (8190-4064)/2 = 4126/2 = 2063